The Chettinadu region has found a place on the UNESCO World Heritage list for its palatial architectural style and rich cultural repository. The mansions or veedu as the locals call it are known for their spaciousness, courtyards, arai (rooms), intricately carved doorways, marble tiles, Italian chandeliers, Belgium mirrors, Burma teak pillars and crockery from South East Asia. But for Amar Ramesh, the humble mogappu was what caught his attention.

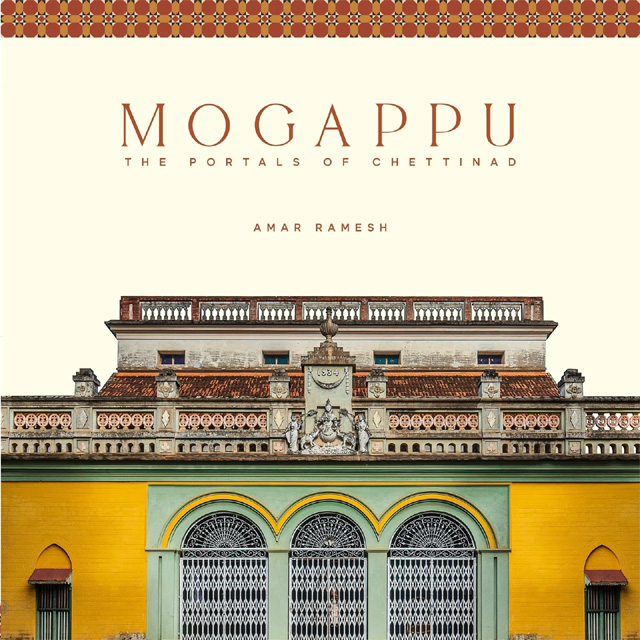

These entranceways are an integral element of the Chettinad household, and each one is truly unique. The entrance ways are clearly a sign of the wealth, status and belief systems of each family. A part of the compound wall, these entranceways added much colour, charm and character to the narrow lanes found in Chettinad villages.

“What drew me to the mogappu were the bright colours and the grand and sometimes unique statues. The statues were made of sudhaia.k.a stucco – a technique widely used in temples of that time aswell,” says the author.

The word mogappu is a combination of two Tamil words – Mugam (face) and Amaippu (the final look). In the Chettinad region, the nagarathars use mugappu to refer to the entrance of the home – to be specific from the gate to the main door.

Through his book, Amar has tried to showcase the mogappus in villages like Karaikudi, Siruvayal, Kanandukathan, Chokkanendal, Kuruvikondanpatti, Athangudi, Rangiyam, Avanipatti, Konapet, Sembanur, Keelasevalpatti, Sokkanathapuram, Panyapatti, Sakkanathapuram and more. “But there is so much more. We have so many more images that we captured, than what is in the book,” he reflects.

Clearly religious sculptures were an integral part of these designs, most often we spot a Gajalakshmi, Shiva & Parvathi, Krishna with Bama Rukmini, Murugan with Valli Deivannai to name a few. As a pious community, the nagarathars believed in surrounding themselves with divinity, so it starts from the entrance. In some homes, there is a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, British royalty and soldiers.

If you’ve spent time in the homes around Chettinad, you’d have heard the aachis say, “moppulairukkaanga” (they are in the mogappu, meaning front portion). “In the earlier days, the mogappu was exclusively for men to sit, converse and even do business. Women did not use the mugappu to enter the home, rather they had a side entrance to reach the far end of the home, which was their quarters back then” recalls R Vairavan chettiar. His ancestral home, known as RM.M.ST House in Devakottai was built in 1923. “Our homes had kanakkapillais (accountants) who would sit in the mugappu. Their role extended beyond writing accounts, and they would meet and greet people; guests and staff would meet the kanakkapillai and then only come into the main hall and meet the Chettiar if he is home,” he says.

As you scan through the pages, you will notice the colour, motifs, jaali work (lattice) and texture. Some homes reflect a grand past, and some an uncertain future. Documentation, like what Amar has done, can only do two things: one rekindle a spirit (not just among nagarathars) to view their ancestral homes in a different light; and second start a conversation on preservation and restoration.Like I’ve always said, we need to keep the conversation going, for positive change to begin.

This book is a keeper.

The book, just a few copies left, can be ordered through https://amarramesh.com/mogappu/